Not only since the German government’s energy-saving campaign (“Dear 80 million“) have we been swamped with well-intentioned advice on how to reduce our personal carbon footprint. Most of these checklists are wild collections of measures with dramatically different effects and questionable persuasiveness. At least that’s what I thought, so I set out to prove in a series of tests that simple adjustments could improve the impact of these lists. And in doing so, I came across a whole series of surprises…

In the following I would like to show that

- these checklists are currently a central dimension of climate communication,

- we climate activists can make them measurably more effective, and that

- systemic measures for frequent polluters can also be communication measures.

I will do this in the form of five catchy hypotheses, each of which I will then justify in detail and in an evidence-based manner.

1. Steer climate communication away from the general climate crisis!

In a nutshell: The question is where best to deploy our scarce climate communication resources with the greatest impact for the climate. Let’s face it: the battle to interpret the climate crisis has been won. We can now redirect the focus of climate communication.

For decades, there have been evidence-based, helpful recommendations on how to convince people that the climate crisis is caused by us (wonderfully summarized on the Skeptical Science website, communication advice for IPCC researchers, university checklists, TED Talks, etc.). Apparently, they have had an impact: even in the U.S., the percentage of citizens who are “alarmed” or “concerned” about the climate crisis has increased from 38% to 53% since 2012 (Yale Program on Climate Communication). In Germany, too, not least the PACE study has shown that we have won this battle: Almost 60% of German citizens are even concerned that we will not meet the climate targets (stable since April 2022, strong/very strong concerns: 36%).

Let’s face it: There will always be a small group of climate deniers whom we can hardly convince (see also interview on klimafakten.de). However, it is not worthwhile to invest in communicating with this fringe group, because the effort required to convince them is just not worth it.

If we want to put our scarce climate communications resources where their leverage for climate is greatest, three areas are promising:

- Policy makers (for the legal framework of system change).

- Economic decision makers (for supply-side system change).

- Personal actions by citizens (for demand-side system change).

In what comes next, I focus on the second area, not because it necessarily has the most impact, but because of my expertise in behavioral economics.

2. Focus on measures, not on climate knowledge!

In a nutshell: The fact is that we don’t really know what we personally can do to combat the climate crisis effectively. And we are systematically lying to ourselves in the process. Changing that is difficult, and more knowledge does not seem to help. Therefore, our climate communication needs to focus on what we can do about the climate crisis.

In 2019, I asked 5000 people in four countries to choose the one with the biggest CO2 impact from a list of seven personal actions. The result was shocking and found its way into many media: giving up plastic bags was at the top of the list in all countries:

This result has been reproduced several times since then (e.g. by Stiftung Warentest) and I also repeated the survey in the U.S. in early 2022 with almost identical results. This means that not only do we have no idea, but also that this is not improving (even in the PACE survey there is only a small increase in climate knowledge since August 2022).

One aspect of this problem is that we not only lack understanding but also choose to ignore it intentionally (perhaps to be able to even look in the mirror in the morning?). Here are two empirical findings:

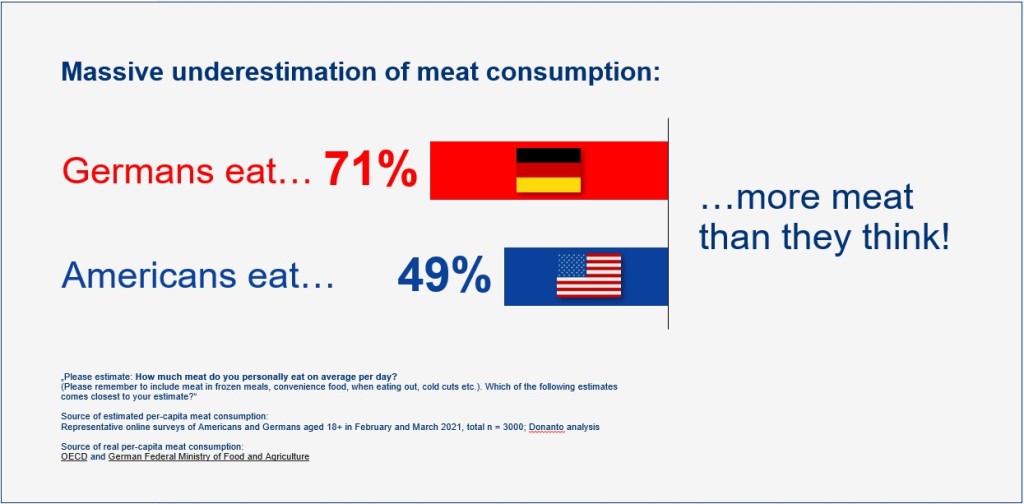

In 2021, I had 3000 people in Germany and the USA estimate their average meat consumption. When comparing with the real consumption data, it turned out that we Germans eat 77% more meat than we are willing to admit:

According to the PACE study, although almost half of the respondents consider their own climate protection to be effective (Top 2 Box: 22.5%), this does not really correlate with the actual climate-friendly behavior of the respondents (0.33)!

The good news – that’s not a problem, because knowledge does not help: The PACE study uses sophisticated analyses to demonstrate that better climate knowledge is only a very weak driver of personal willingness to act! This is probably the most explosive result of the whole study, but it fits seamlessly into my findings.

3. Focus only on effective measures!

In a nutshell: We ignore even simple help in selecting personal measures against the climate crisis. Which of the selected measures we then actually implement depends neither on their effect nor on their simplicity. Unfortunately, we can only be motivated to take two or fewer measures on average, so all too often, we select measures with little effect.

Our climate communication should therefore only address the most effective measures against the climate crisis and should deliberately omit the less effective ones.

Numerous checklists of personal measures hardly mention anything about the size of the respective CO2 savings. I have always wondered how one is supposed to select the right measures without this information. But the solution is obvious – I thought: You add information on CO2 savings to the checklist and sort it according to the strength of the effect.

To measure the extent of improvement, I presented such an optimized checklist to 1000 people and asked them to select the measures they wanted to follow themselves. 1000 other people (again, representative of German online users) were shown the original checklist (without CO2 savings, measures in randomized order). The comparison of the results was shocking (see the following figure as an example): Sorting and information did not lead to any improvement in the choice of measures! And it was particularly shocking that most of the respondents still selected plastic bags, although it was clearly visible that the CO2 effect is negligible!

One obvious assumption is that we choose the measures that we find particularly easy to implement. But the results of my survey already cast doubt on this, namely when heating replacement (costly, time-consuming) is chosen more frequently than switching to green electricity (cheap, quick). In fact, according to the PACE study, many measures do not differ in their perceived simplicity by the respondents, only “climate-friendly home appliances” are rated slightly more difficult (3.7 out of 7) than the other measures (~4.5 out of 7):

Or consider the following evidence: The “Climate Bet” campaign tried to get people to take effective climate-friendly actions. At the end of this campaign, a survey asked which of the originally selected measures were actually implemented by the respondents in their everyday lives. It turned out that the degree of implementation correlated neither with the popularity or simplicity (=initial selection) nor with the effectiveness of the individual measures:

That wouldn’t be a problem if each of us took a variety of actions to combat the climate crisis. However, in about a dozen surveys in several countries with a total of more than 10,000 respondents, I have not once managed to get respondents to take more than two actions on average! The average is 1.5 measures, regardless of whether one asks about one’s own plans or about the less socially desirable question of what measures friends and acquaintances are likely to take. In addition, the “spillover” effect from climate-friendly measures to further measures is very difficult to achieve in reality, as the EU-wide CASPI project has shown.

Thus, if our advice simply omits the less effective measures, the climate impact of climate communication can be dramatically increased, as the following two surveys show by comparison:

I conducted a similar test based on the BMWK campaign in August 2022 with 2000 respondents, using the BMWK measures and wording: Focusing on the more effective measures did persuade significantly more respondents to pursue an effective measure (in this case, heating one degree less):

The one-minute commercial by Leaders for Climate Action therefore does everything right from this perspective! The next question is whether this is enough for success.

4. Focus on viral climate communication!

In a nutshell: Even well-done climate communication is too expensive using classic marketing means if it is to have a measurable climate impact at the national level. Viral campaigns in social networks are a possible alternative to roll out effective climate communication at a reasonable cost.

The “Climate Bet” campaign (see above) ended in great disappointment despite its excellent ideas: Of the targeted 1 million (saved or offset) tons of CO2, only around 20 thousand were achieved. Was this due to a lack of marketing know-how? Let’s take a look at a different campaign: In 2021, Leaders for Climate Action (LFCA) succeeded in generating 24 million contacts with its climate communication within a very short time through a large partner network of digital companies. The majority of these contacts were generated via campaign banners on partner sites and they generated almost 200 thousand visits to the campaign website. However, this only resulted in 15 thousand self-commitments to climate actions. So, despite impressive media presence, this outstanding campaign only persuaded a tiny fraction of German citizens to take climate-friendly action:

The marketing figures for this campaign are quite respectable (0.8% click-through rate and 7% conversions on the landing page). This is also evident when comparing it to key figures of the 2022 campaign: There, LFCA was able to reach 85 million people, but the number of people who registered for concrete climate protection measures on the landing page was still in the range of a few thousand, not least because the marketing metrics had deteriorated (0.2% click-through rate, 3% conversions).

A simple “back-of-the-envelope” calculation shows the resulting challenge of classic marketing communication:

Let’s assume we want to persuade enough citizens to take personal action that the effect would be measurable nationwide. To do this, we need – conservatively estimated – at least 10 million people who implement at least one effective measure, e.g., heating one degree Celsius less. If we apply the marketing metrics of the LFCA campaigns (see above), we would need to generate between 125 to 333 million clicks online for this. With common costs of 0.5 to 1.5 € per click (“CPC”), the pure communication costs for this one measure would therefore be between 62 and 500 million euros! By comparison, the BMWK campaign cost around €33 million by the end of November 2022, and Germany’s largest advertiser, Procter & Gamble, spends just over €1 billion a year on advertising. This means that measurably effective climate communication using classic marketing tools is simply too expensive for most players.

Would a PR strategy (i.e., distributing the measures via editorial contributions in the media) be an alternative? The PACE study has shown that trust in the messengers of climate communication is a key driver of willingness to act. Unfortunately, the PACE study also showed that trust in public service broadcasters is similarly poor to trust in the federal government (3.4 out of 7 on a scale of 1 – very little trust – to 7 – very high trust). In contrast, trust in “people and groups who share content on social networks” is significantly higher (4.3 out of 7; trend: increasing).

Therefore, the only way to have measurably effective climate communication at a reasonable cost seems to be via viral campaigns in social networks. (I described a possible approach to this in my TEDx Talk.) In viral communication campaigns, readers themselves take charge of spreading the messages, typically at no additional cost, via social networks and/or electronic messaging, so that no further media budget is required. Unfortunately, this is easier said than done, not least because research in this area is still in its infancy. Meaningfulness of the content and emotional arousal motivate at least some of the readers to forward (cf. Borges-Tiago et al. 2019, Botha, Reyneke 2013)

5. Focus initially on actions targeting heavy polluters!

Heavy polluters such as frequent flyers contribute disproportionately to the climate crisis, but it has been proven that they can hardly be reached by exhortations. Systemic measures such as progressive increases in the cost of frequent flying are an effective lever in this area and are likely to increase acceptance of measures that affect the general public.

The higher our income, the higher our expenditure, the more we consume and the larger our CO2 footprint (depending on the country and time period, a 10% increase in income increases the CO2 footprint by 6 to 8%, see meta-study by Pottier 2022). This leads to a gap in the CO2 footprint between high and low income households by a factor of 10 or more (see Weber, Matthews 2008). An important driver of this is personal flight behavior. As an example, I have calculated this using Lufthansa’s frequent flyer program: The flights that get you “Lufthansa Senator” status quadruple (!) your personal carbon footprint, compared to the national average:

It is estimated that the number of German frequent flyers is between 50 and 150 thousand people, significantly less than 1% of the population. A new study by Cass et al. 2023 diagnoses, based on in-depth interviews and focus groups with this target group, that “high-energy consumers may never voluntarily respond to information, exhortations, and appeals to self-interest. Instead, stronger state actions including those that impinge on ‘consumer freedoms of choice’ are required.” (My own experience with friends and family fully confirms this.)

Thus, if personal measures fail for high-energy consumers, systemic measures are needed, e.g., progressively increasing the cost of frequent flights through taxes or even limiting flights per person. Acceptance according to a 2018 survey by Kantenbacher et al. is higher for taxation (3.1 vs. 2.7 on a scale of 1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree). The PACE study also showed that “taxing millionaires” (with the purpose of helping poorer countries meet climate change standards) receives significantly higher support than bans on certain modes of transportation (strong/very strong support: 61% for taxing millionaires vs. 34% for banning internal combustion engines from 2030).

In general, “pull” measures (e.g., financial incentives) have a higher acceptance than “push” measures (e.g., bans), cf. Drews, van den Bergh 2015. It will come as no surprise that support for any systemic measures drops significantly once respondents are traveling by air themselves (Kantenbacher et al. 2018, Hammar, Jagers 2007).

My hypothesis is that systemic measures for frequent flyers increase the overall acceptance of general measures that affect everyone because it increases perceived fairness (even though this aspect has not yet been studied in a dedicated way to my knowledge, there is empirical evidence for it, see Cai et al. 2010, Brannlund, Persson 2012, Gampfer 2014, Carattini et al. 2018). Therefore, systemic actions against heavy polluters can be key tools of climate communication to prepare the ground for broader action.