When Decisions Get Hacked

- Introduction

Let’s focus on what unites us for a change, shall we? Climate change is a transatlantic headache – big, messy, and guaranteed to spark arguments at dinner parties. Europeans love a good regulation, preferably wrapped in a 300-page report and debated over espresso. Americans, on the other hand, prefer innovation and market-driven solutions, often with a side of “we’ll fix it with technology.” Yet, despite these cultural quirks, both sides wrestle with the same fundamental dilemma: How do we make real progress without torpedoing economies? How do we keep people on board without triggering social media outrage? And most importantly, how do we stop talking about solutions and actually implement them before Miami turns into Venice?

- Hacking Humanity, One Nudge at a Time

Our most crucial decisions – be it in courtrooms or at climate summits – are vulnerable to tiny, well-timed nudges. Dozens of studies reveal that small, almost imperceptible changes can alter opinions as swiftly as a viral tweet. A study on 1,112 parole decisions found that judges were dramatically more likely to grant parole after their coffee break and lunch – suggesting that even critical legal outcomes can be influenced by something as simple as hunger. If justice can be swayed by a sandwich break, what does that say about our ability to make sound decisions on something as complex as climate policy? Imagine a policy proposal on CO₂ pricing facing the same kind of arbitrary fate, its success dependent not on scientific merit but on the timing of the vote or the mood of the electorate. In both Europe and the U.S., this hackable nature of decision-making forces us to ask: are we really making informed choices, or are we just following the well-timed taps on our shoulders? And if so, how can we use this approach to get us where we need to be?

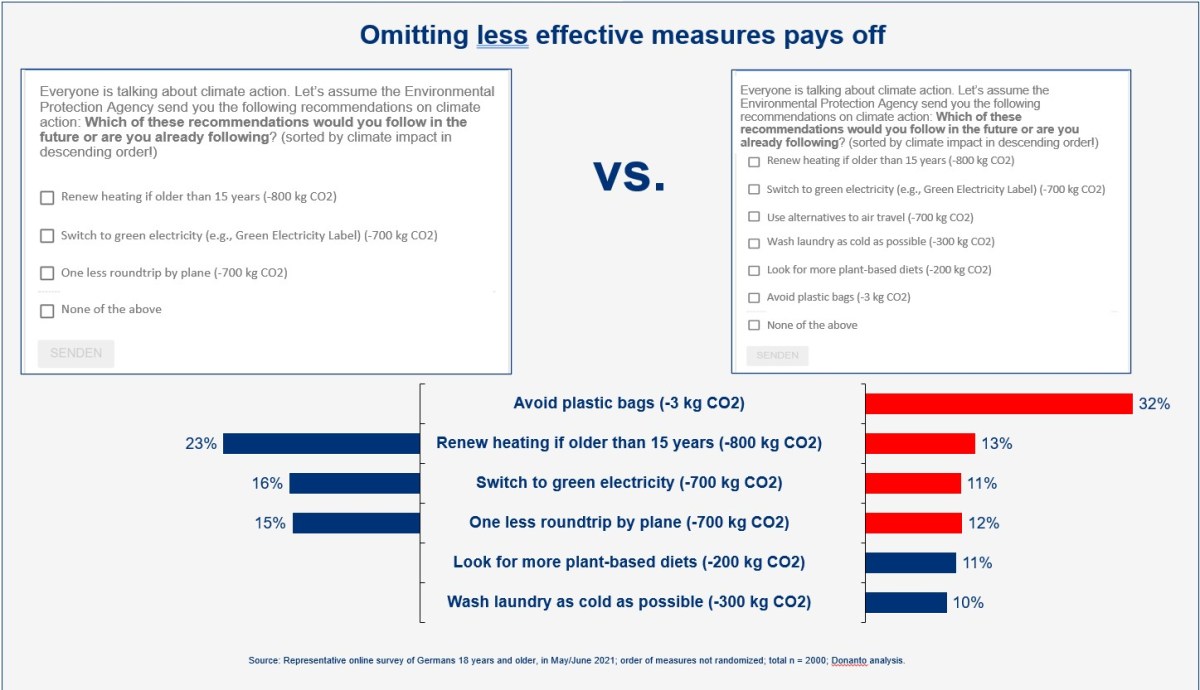

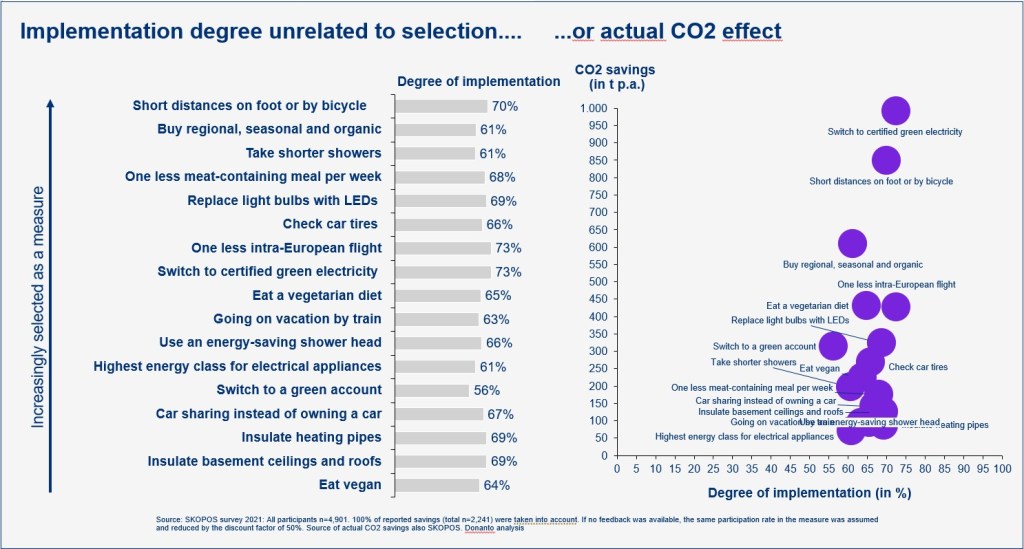

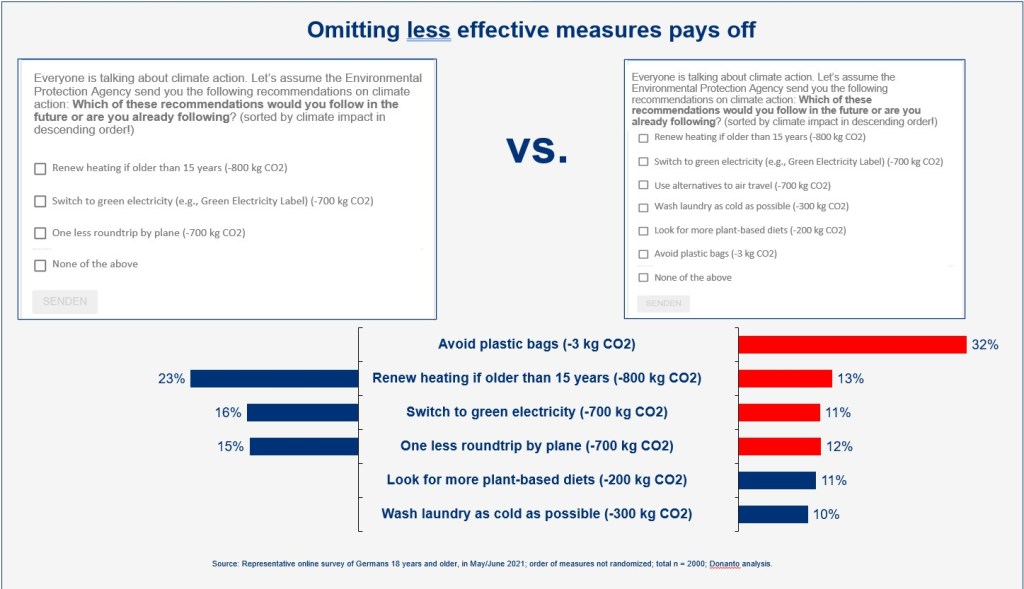

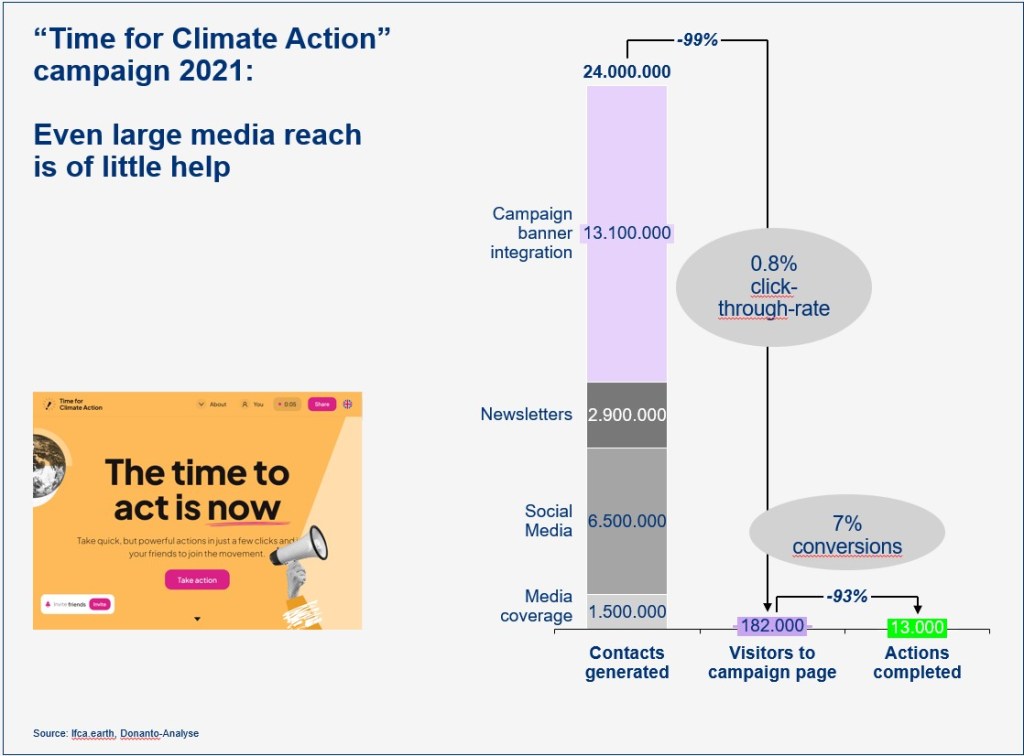

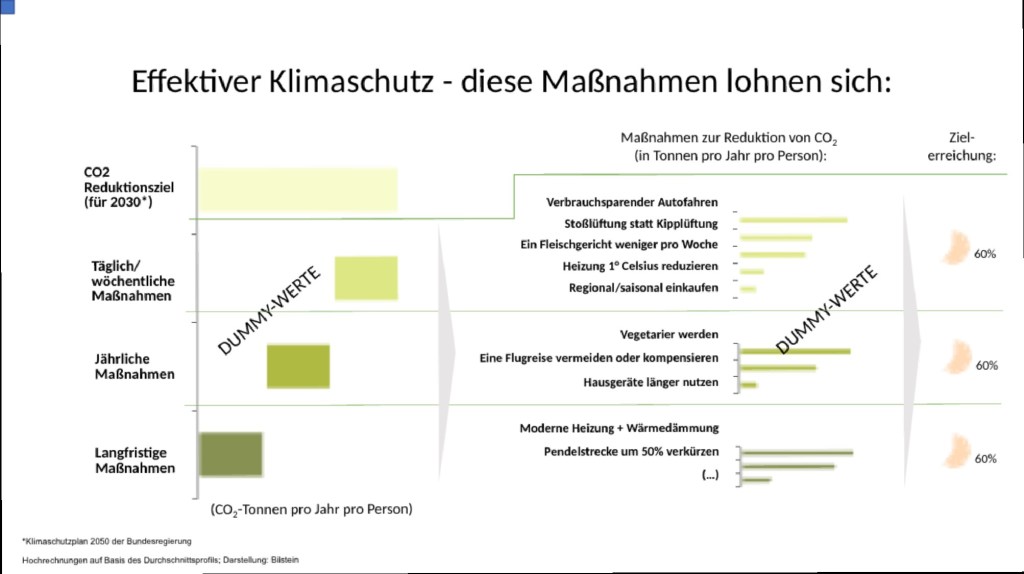

Here is a recent example from my own research: I noticed in a number of surveys with thousands of Americans and Europeans that whenever low-impact measures are presented alongside high-impact ones, the duds tend to dominate attention – regardless of their actual effectiveness. This cognitive trap dilutes focus and weakens outcomes. Therefore, the smart move is to leave the low-impact fluff off the menu entirely – because if it’s on the table, it steals the spotlight.

- A Side of Meat: Appetite, Underestimation, and Transatlantic Taste

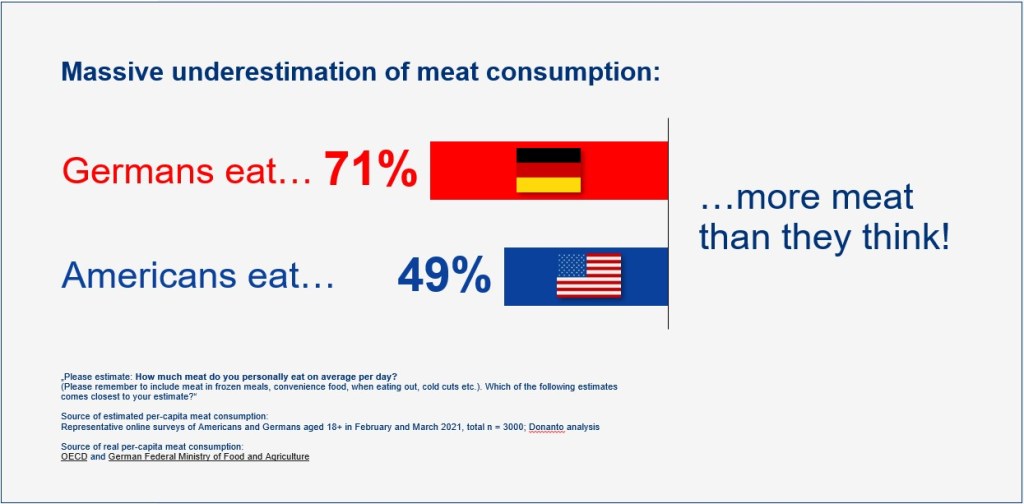

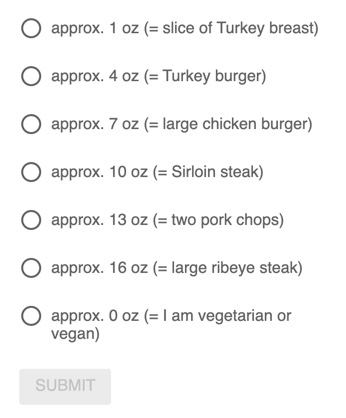

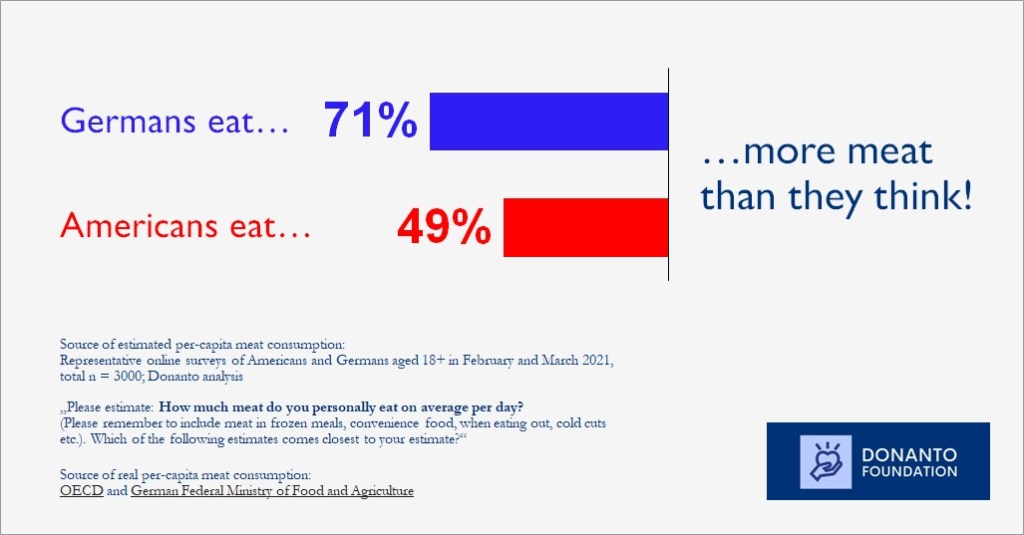

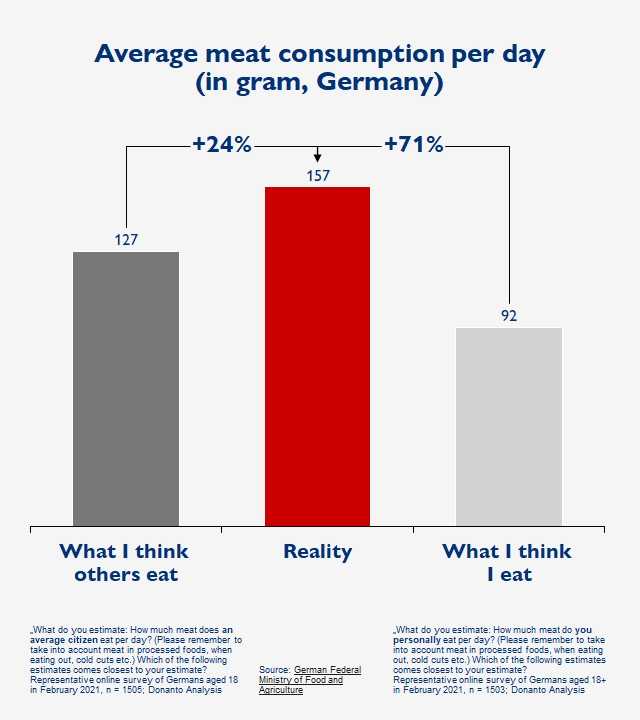

One facet of our climate conundrum is that we sometimes just deny reality. My corresponding example comes served with a generous helping of irony – meat consumption. My surveys with more than 3,000 respondents indicate that both Americans and Germans dramatically underestimate how much meat we actually eat, but there is still a difference: Germans eat 77% more meat than they think, while Americans eat close to 50% more. In Europe, this underestimation might be a nod to a more measured approach, as if to say, “Yes, we consume, but we consume with restraint.” Across the Atlantic, however, the unspoken truth is that the U.S. may be feasting on burgers with an almost celebratory abandon. This disparity not only provides fodder for humorous banter at dinner parties but also highlights a deeper cultural divergence: while Europeans might engage in polite self-deprecation about portion sizes, Americans often have a robust, unapologetic appetite that spills over into their approach to policy and law.

- Facts, Figures, and the Illusion of Knowledge

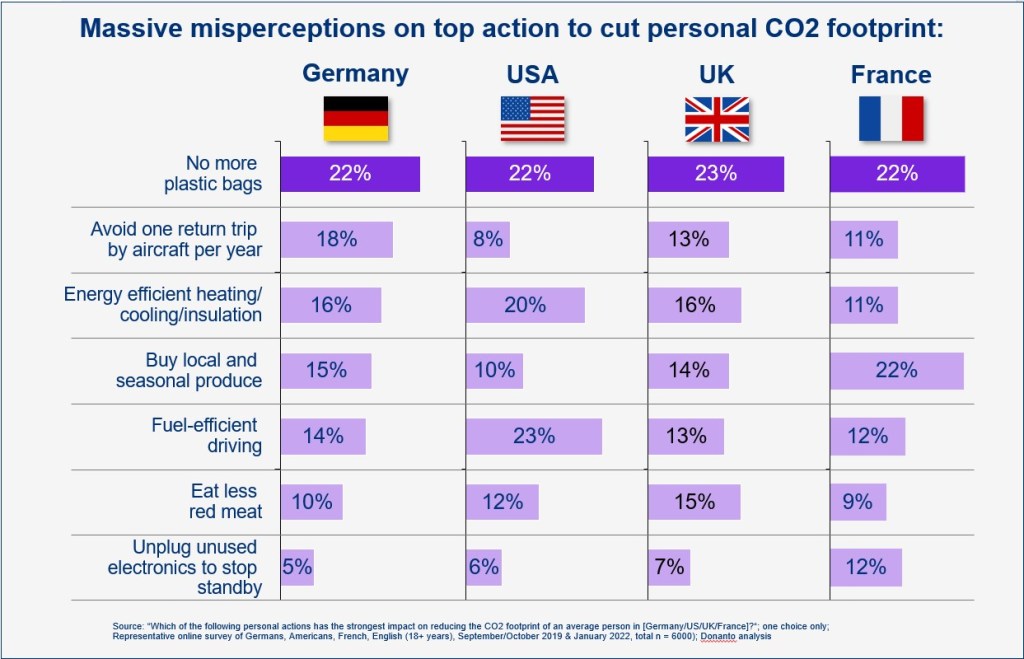

One might think that more information equals better decisions, but it’s not the sheer volume of climate facts that matters – it’s understanding the effectiveness of the measures we propose. That is one of the key insights of a new multinational study with more than 40,000 respondents. Whether it’s a CO₂ price mechanism paired with transfer payments or a complex legal reform, the key lies in knowing what works. The study showed that there was only a limited difference between the U.S. and Europe regarding this point. Now take a second and consider the last pieces of information you saw on climate issues. My bet is that, most likely, you were fed facts on the climate crisis as opposed to explanations on effective policies.

- Fairness: The Unwritten Law in Policy and Precedent

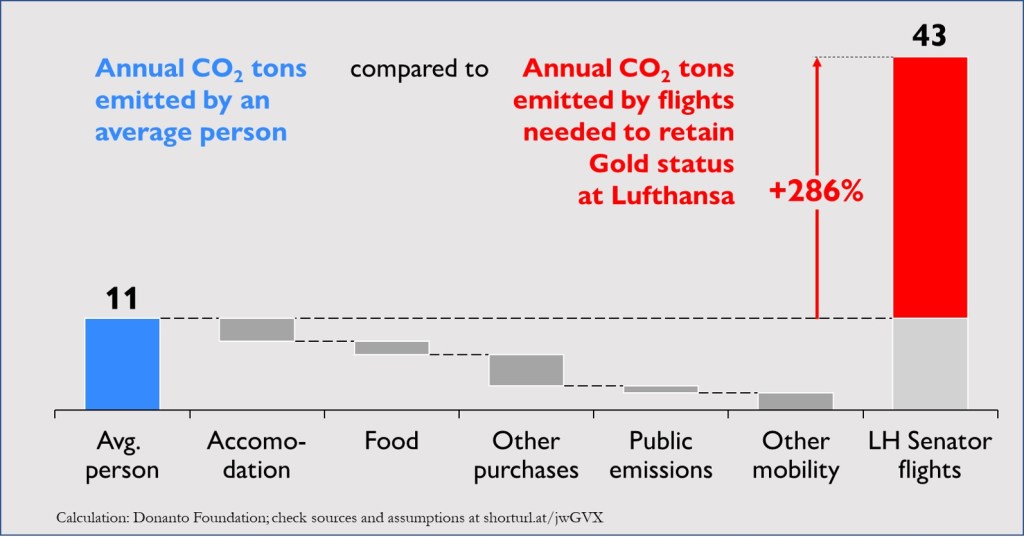

At the heart of effective policy – be it environmental or legal – is a deep-seated sense of fairness. Unfortunately, only about a third of respondents in high-income countries like the U.S. and Europe consider a carbon tax with cash transfers to be fair! The most important factor in all countries (surveyed in the study mentioned above) that encourages climate-friendly behavior adoption is “The well-off also changing their behavior”! So, even amidst ideological clashes, both Europe and America ultimately converge on the idea that a policy perceived as unjust is doomed from the start. Whether you’re drafting a judicial decision or a climate policy, fairness isn’t optional – it’s the foundation upon which trust and acceptance are built. However, this is just one aspect of what makes a climate policy effective.

- Cutting the Fluff: Focusing on What Truly Works

Imagine wading through 1,500 governmental climate measures only to find that a mere 63 are truly effective. That’s the arduous work done by a team of researchers led by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, using an incredibly sophisticated machine-learning based approach. The takeaway here is strikingly clear: only very few policies were effective. In both legal and climate arenas, it’s about trimming away the excess and focusing on what works. Rather than indulging in an overload of well-intentioned but largely ineffective initiatives, both American and European policymakers could benefit from a more discerning approach.

- Bundling: The Secret Sauce of Policy Success

According to the study, successful state actions often come in tailor-made bundles. Think of it as the policy equivalent of a perfectly crafted cocktail: each ingredient, from strict emission regulations to economic incentives, plays a crucial role in delivering a satisfying punch. Both, in Europe, as well as across the Atlantic, while there are certainly attempts at such integration, the process sometimes feels more like an improvisational jazz session than a rehearsed symphony. The lesson? Whether in law or climate policy, crafting a winning strategy is less about isolated acts and more about the harmony of a well-curated ensemble.

- The Transatlantic Tango: Differences and Similarities

The transatlantic divide resembles an elaborate dance, where each side steps to a different beat yet shares the same stage. The Europeans waltz through policy debates with meticulous precision and overengineering (Green Deal, CSRD, etc.). Their American counterparts, on the other hand, often prefer a more freestyle approach – bold, brash, and occasionally a tad chaotic. Despite these stylistic differences, both continents are united by a common thread: an unwavering commitment to addressing the climate crisis, even if the methods vary – and even if public perception is at times different.

- Reflections on Hackable Decisions and the Future of Policy

If there’s one thing to take away from this whirlwind tour of transatlantic policy, it’s that our most vital decisions are not immune to manipulation. Whether it’s the nuanced interplay of nudges in a judge’s decision-making process or the subtle persuasion embedded in climate communication, we are all, in some ways, victims of a hackable human nature. And yet, this vulnerability also presents an opportunity. By understanding the levers that drive behavior – be it fairness, effective communication, or the clever bundling of initiatives – we can design systems that not only mitigate the risks but also harness our collective potential for positive change.

Looking forward, the challenge for both European and American policymakers is to embrace these insights without losing sight of what makes their approaches unique. In either case, the goal remains the same: to turn our hackable human nature from a liability into a strength.

So, let’s stop serving climate side salads and start dishing out the main course. If Brussels obsesses over straws and Boston ignores heat pumps, we’re all just rearranging deck chairs – real progress demands focus on what cuts carbon at scale.

(This article was initially published in the Transatlantic Law Journal, Volume 3, Issue 4, p. 145ff. My thanks go to the editors for allowing me to post it here!)